Books

In Progress: Cities Purged: The Nazi Campaign against Judeo-Bolshevism

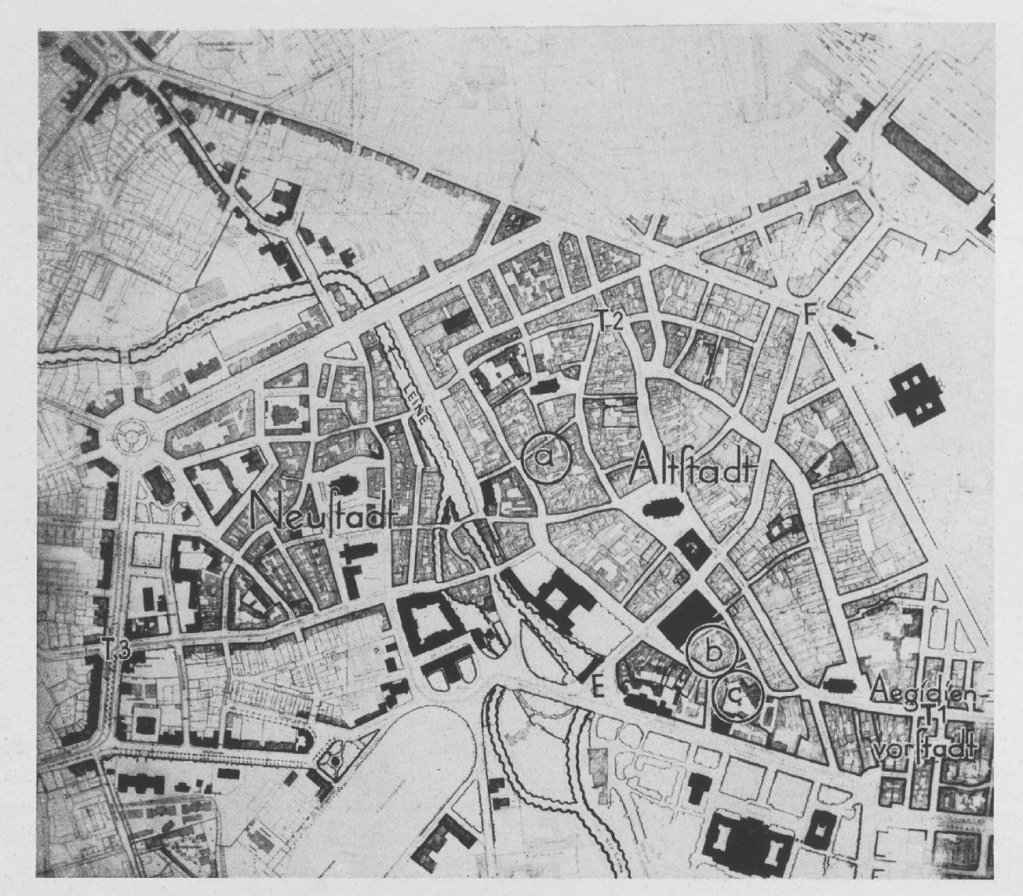

My first book manuscript sits at the intersection of intellectual history, cultural history, and urban history. In the book, I argue that Judeo-Bolshevism, the antisemitic myth which purported that Jews had devised bolshevism, was the central pillar of Nazi ideology and that this ideology was an embodied concept inextricable from the modern city. In the early twentieth century, Nazis claimed that Germany, especially its cities, had become “jewified” (verjudet) and infected by political and cultural bolshevism. To counter this contamination, Nazi officials endeavored to cleanse urban spaces—physically, symbolically, and rhetorically of Judeo-Bolshevism.

At first, the Nazi regime broadly targeted spaces that it associated with political and cultural bolshevism—Communist and Socialist party headquarters, trade union houses, art schools, homosexual meeting sites, and pacifist and free-thinking organizations. Early practices of spatial cleansing at these sites included vandalization and destruction, confiscation and repurposing, redesign and renaming, as well as urban renewal. Increasingly, however, this campaign against Judeo-Bolshevism more intently targeted Jews and explicit Jewish spaces through demolition, bans and segregation policies, and eventually, expulsions and deportations. Haphazardly at first, and later more systematically, this project of spatial cleansing was implemented in Germany and then beyond its borders, acquiring greater dimensions and more radical and lasting solutions during World War II and the Holocaust.

My book is the first to write an explicit urban history of National Socialism, one that shifts the focus of current historiography from spatial cleansing in wartime eastern Europe to urban spaces in interwar Germany. In doing so, I show how practices of spatial cleansing that led to genocide were devised, tested, and implemented in German cities during the 1920s and 1930s.

Räume der deutschen Geschichte (Spaces of German History), 2022

German history in the past decade has experienced a “spatial turn” as scholars have analyzed, in particular, how ideologies concerning race and space informed World War II and the Holocaust. Further research has expanded the temporal scope beyond 1933–45 to underscore how the concept of “space” has been critical to Germany throughout its entire modern history. Scholars have historicized late nineteenth-century spatial thinking regarding landscapes, nature, identity, and borders as evident in processes of modernization, territorialization, colonization, nationalization, and globalization. Postwar historians have likewise examined how Cold War ideologies reshaped German spaces (state buildings, housing complexes, and landscapes) and how individual interactions within space reinforced the Iron Curtain and Germany’s internal and external borders.

This volume brings together diverse scholars working at the intersection of modern Germany and spatial history. The authors are historians who investigate ideas about space, claims to space, and practices within space in modern German history. They examine diverse topics such as space, place, borders, landscapes, territorialization, intellectual history, environmental history, urban history, and visual and material culture. Collectively, the contributions in this volume underscore the indispensability of space as an analytic category for Germany history. They illuminate how questions of space have shaped and reshaped Germany in the modern era.

Full Citation: Walch, Teresa, Sagi Schaefer, and Galili Shahar, eds. Räume der deutschen Geschichte. Tel Aviver Jahrbuch für deutsche Geschichte. Vol. 49. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2022.

Articles

“Orchestrating Consent: Public Space and the Nazi Consolidation of Power“

This article examines the “Nazification” of public space in the early months of 1933. I argue that the Nazi regime successfully employed public space to legitimate its power and orchestrate the Volksgemeinschaft. The regime banned all symbols of oppositional groups from public spaces. Thereafter, the regime, under the direction of Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, perfected its use of cityscapes to manifest its authority during several momentous occasions in the winter and spring of 1933. Germans were encouraged, and pressured, to demonstrate visible loyalty to the Nazi Party by adorning streets, buildings, windows, and balconies with swastika flags and greenery. Through these measures, the regime manufactured a robust façade of consent in public space. It was both a voluntary and coercive endeavor that was designed to include “racially fit” members of the German national community while excluding German Jews.

Full Citation: Walch, Teresa. “Orchestrating Consent: Public Space and the Nazi Consolidation of Power.” In Räume der deutschen Geschichte, edited by Teresa Walch, Sagi Schaefer, and Galili Shahar, 115-143. Tel Aviver Jahrbuch für deutsche Geschichte. Vol. 49. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2022.

“With an Iron Broom: Cleansing Berlin’s Bülowplatz of ‘Judeo-Bolshevism,’ 1933-1936“

Home to the Communist Party of Germany’s headquarters and heart of the remaining Scheunenviertel and its Jewish populations, Berlin’s Bülowplatz was detested as representative of ‘”Judeo-Bolshevism” by local Nazis, and they vowed to “cleanse the square with an ‘iron broom’. In March 1933, SA-men and police officers occupied and confiscated the KPD headquarters and renamed the square “Horst-Wessel-Platz.” Thereafter, city officials selected the Jewish-owned apartment buildings behind the square for the first urban renewal measures under the new regime, with the explicit intent of evicting the Jewish residents from this Nazi memorial square. Via a close reading of minutes from bureaucratic meetings, this article illuminates how bureaucrats began translating Nazi ideology into practice. Although municipal and federal bureaucrats initially lacked the requisite authority and legislation to implement this ideologically driven project, united by broadly held antisemitic prejudices they creatively devised solutions and collaborated to mobilize bureaucratic processes for city planning that was explicitly antisemitic. The ideological transformation of Bülowplatz constituted the earliest case of de-Jewification (Entjudung) in Nazi Germany and set an important precedent for later measures of spatial and ethnic cleansing enacted against Jews in Germany and across Europe.

Full Citation: Walch, Teresa. “With an Iron Broom: Cleansing Berlin’s Bülowplatz of ‘Judeo-Bolshevism,’ 1933-1936.” German History 40, no. 1 (March 2022): 61-87.

“Kampf um Raum: The Raumwirtschaft & Spatial Hierarchies in the Theresienstadt Ghetto“

The Nazi propaganda film, Theresienstadt: Ein Dokumentarfilm aus dem jüdischen Siedlungsgebiet, presents a distorted and carefully orchestrated rendition of life in the Theresienstadt Ghetto. The film scenes that depict ghetto housing, often dismissed as a product of the superficial “beautification” measures carried out in Theresienstadt, nonetheless invoke the spatial hierarchies that existed in the ghetto. As the densest ghetto, Theresienstadt’s “spatial problem” was perpetually acute, and the Raumwirtschaft (Space Management Office) was established to closely monitor the use of available space and to manage the living accommodations of ghetto inmates. Drawing upon a wide set of archival records and ego documents, this article examines how Jewish inmates navigated everyday life amidst an acute shortage of space and argues that space was an important ghetto commodity that radically reshaped communal relations in Theresienstadt.

Full Citation: Walch, Teresa. “Kampf um Raum: The Raumwirtschaft & Spatial Hierarchies in the Theresienstadt Ghetto.” In Filmfragmente und Zeitzeugenberichte: Historiographie und soziologische Analysen, edited by Laura Kellner, Hans-Georg Soeffner, and Marija Stanisavljevic, 21-48. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2021.

“Just West of East: The Paradoxical Place of the Theresienstadt Ghetto in Policy and Perception“

When German authorities established the Theresienstadt Ghetto for Bohemian and Moravian Jews in late 1941, the site initially functioned much like other ghettos and transit camps at the time, as a mere way station to sites of extermination further East. The decision to reconfigure the ghetto as a site of internment for select “privileged” groups of Jews from Germany and Western Europe, and its advertisement as a “Jewish settlement” in Nazi propaganda, constituted an apparent paradox for a regime that sought to make the Greater German Reich “judenrein” (clean of Jews). This article investigates the Theresienstadt Ghetto from a historical-spatial perspective and argues that varying prejudices and degrees of antisemitism shaped divergent “spatial solutions” to segregate Jews from non-Jews, wherein the perceived divide between so-called “Ostjuden” and assimilated Western Jews played a central role. In this analysis, Theresienstadt emerges as a logical culmination to paradoxical policies designed to segregate select groups of German and assimilated Western European Jews.

Full Citation: Walch, Teresa. “Just West of East: The Paradoxical Place of the Theresienstadt Ghetto in Policy and Perception.” Naharaim 14, no. 2 (December 2020): 243-264.